Turning Point After Kirk

What the data reveal about Charlie Kirk, young men, and the limits of grievance politics

The Backdrop

This week, Turning Point USA has brought tens of thousands of supporters to Phoenix for AmericaFest, its annual conference and one of the most visible gatherings of conservative activists, donors, media figures, and elected officials in the country. The event is meant to signal continuity and confidence — proof that the movement Charlie Kirk built still has energy, reach, and relevance, especially among young men.

That claim matters. Few figures in recent politics understood how to connect with young men the way Kirk did. He spoke directly to frustration, challenged institutions head-on, and wrapped politics in a sense of belonging. For many young men, the appeal wasn’t policy first — it was recognition and confidence.

AmericaFest makes that energy visible.

What it cannot tell us is whether the ideas on stage have actually consolidated into something durable — or whether they are being held together by performance, personality, and crowd reinforcement alone.

Movements often mistake visibility for coherence.

There is a difference between energy and alignment — between agreeing with parts of an argument and adopting the framework behind it. That difference is especially important when we talk about young men, who can engage intensely without ever fully committing ideologically.

To understand that difference, we looked past the spectacle and tested the ideas themselves — surveying more than 1,000 Americans ages 18–29 and presenting arguments commonly associated with Charlie Kirk and Turning Point USA without labels, branding, or the pull of a crowd.

When those ideas are evaluated quietly, something consistent happens.

Certainty softens.

Young people don’t reject the ideas outright. But they don’t embrace them as a package. They slow down. They weigh. They hesitate.

This isn’t ideological confusion. It’s discernment shaped by experience. A generation that has watched institutions fail repeatedly has learned to test claims before committing to them.

The result is selective agreement, not ideological alignment.

My Takeaways

#1: There Is No Ideological Alignment — Even Among Young Men

As I argued recently in The New York Times, Charlie Kirk understood how to connect with young men around belonging and purpose. What our new SocialSphere analysis shows is what happened next — when that connection was tested for ideological coherence.

If a durable ideological alignment were forming around the ideas Kirk championed, young men would be where it showed up first — the group most closely associated with his audience and outreach.

It doesn’t.

When the ideas associated with Charlie Kirk are tested quietly — without his name, without Turning Point USA, and without the energy of a crowd — young men do not cohere around them as a package. They respond issue by issue, not ideologically.

What’s revealing is why Kirk attracted attention in the first place.

In focus groups, young men who spoke positively about Kirk rarely describe agreement with his ideas. Instead, they talk about how he presented them.

One participant praised him for being “articulate,” noting that he could “explain complex situations in a simple way” and that he “didn’t get emotional or yell.” Another said he appreciated that Kirk would “step back and say, ‘first, we have to set the foundation.’” A third described him as “straightforward,” adding that “you could disagree with him or not, but he gives a lot of data.”

These are not expressions of ideological alignment.

They are evaluations of style, confidence, and delivery.

When asked directly, some participants draw the boundary themselves. As one young man put it plainly: “I agree with parts of them, and there’s other parts that I don’t.”

That distinction explains what the survey data show.

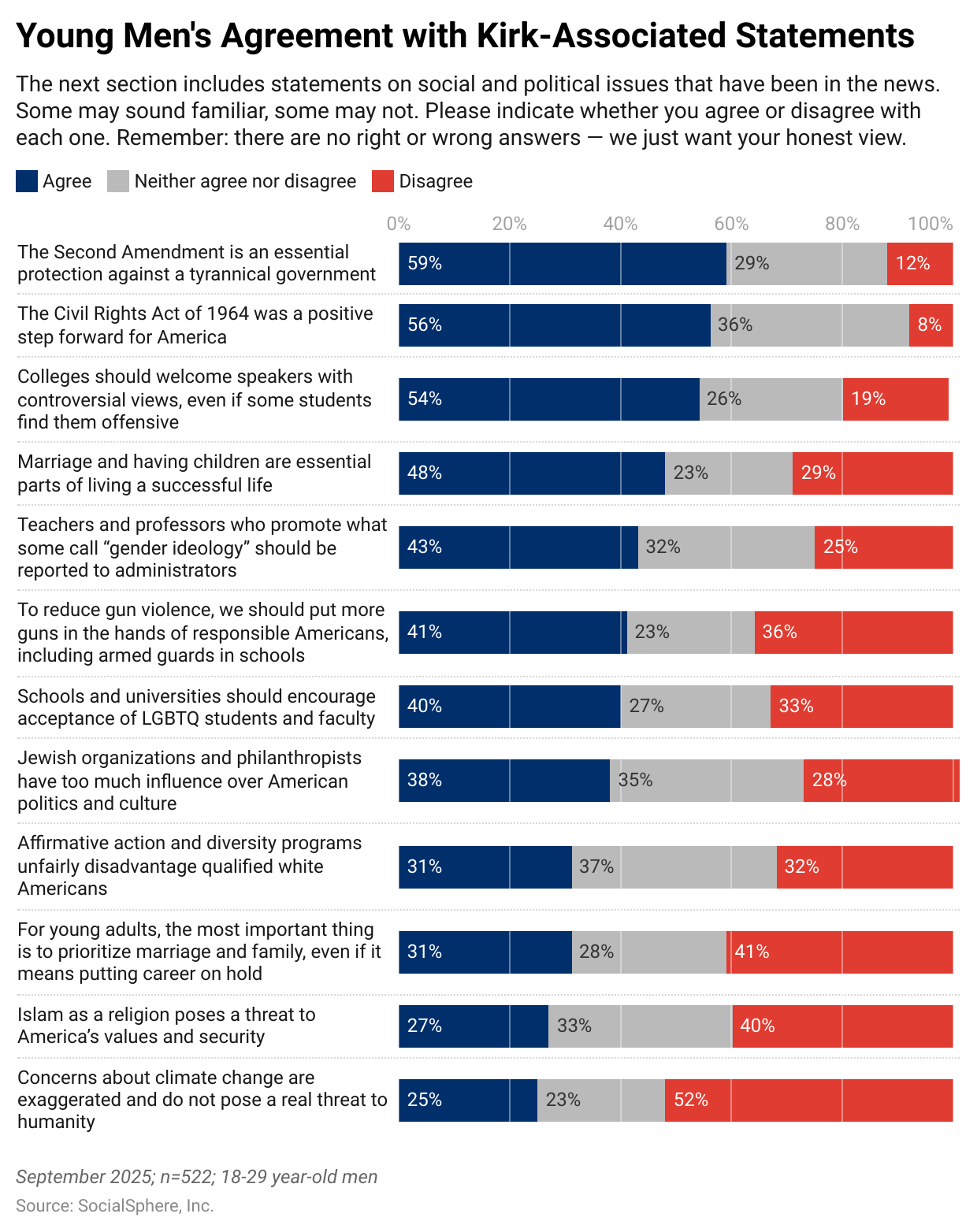

When SocialSphere tested these ideas in our September Gen Z Tracker, agreement among young men failed to consolidate. Only two items reached majority support, both framed as broad protections rather than prescriptions. On every item that implied enforcement, hierarchy, or denial of widely shared risk, support fragmented.

Just as important is what sits in the middle.

Across nearly every statement, a large share of young men neither agreed nor disagreed. That neutrality is not apathy. It’s evaluation.

Young men are listening.

They are not aligning.

What looks like momentum in a room is, in reality, conditional engagement — driven by presentation and recognition, not ideological commitment.

#2: Women Are Not a Growth Opportunity — They Are a Structural Hard Stop

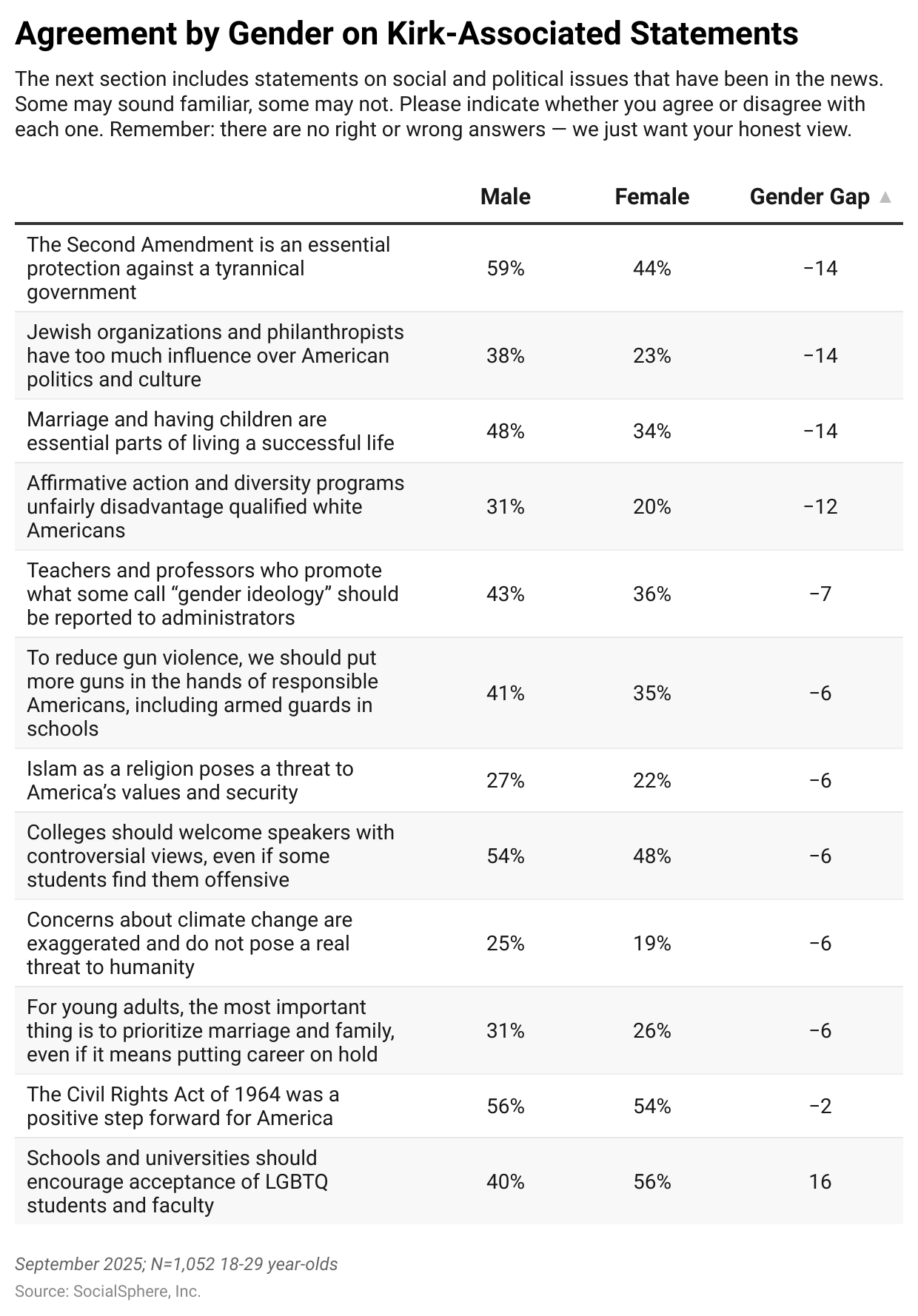

If the first finding shows that ideological alignment never fully consolidates among young men, the second clarifies where the ceiling hardens.

Women do not simply align less.

They evaluate the framework differently — and exit it faster.

This matters enormously in the current moment.

With Erika Kirk now leading Turning Point USA, it’s tempting to assume the movement can broaden its reach — particularly among young women — by adjusting tone, emphasis, or messenger. But the data suggest the challenge is not outreach.

It is fit.

Across nearly every Kirk-associated idea, women are significantly less likely than men to agree. And the pattern isn’t random. The gaps widen precisely where ideas move from critique to constraint — where they imply enforcement, obligation, or increased exposure to risk.

On abstract principles or baseline values, gender differences are narrower. But as soon as an idea suggests monitoring behavior, prescribing social roles, or shifting downside risk onto individuals, women pull back sharply.

This isn’t because women are more ideological. It reflects how risk is processed.

Women in this age group are more likely to be navigating thin margins — financially, professionally, and in caregiving roles — and are therefore more sensitive to second-order consequences. They tend to ask different questions of political ideas:

Who bears the cost if this goes wrong?

What flexibility do I lose if this becomes the rule?

What risk is being shifted onto me?

When a framework can’t answer those questions clearly, women don’t debate it.

They disengage.

For Turning Point USA, this isn’t a communications problem. It’s a structural constraint on how far the ideology can scale.

#3: Frustration Creates Attention — Not Ideology

At this point, the pattern becomes unmistakable.

Young men engage.

Women disengage.

And the framework never consolidates.

To test whether engagement hardens into ideology, we created a Charlie Kirk Alignment Index — a 12-item composite measuring whether respondents consistently align with the full framework across gender, guns, race, religion, free speech, climate, and family.

The results are stark.

Only about 5% of Americans ages 18–29 meet the threshold for consistent alignment. Among young women, alignment at that level is similarly rare.

Nearly half of young men (47%) fall into partial alignment: agreeing with some ideas, rejecting others, and declining to commit to the framework as a whole.

Looking at groups often assumed to form the core of the base doesn’t change the picture — it sharpens it.

Among white young men, 53% show partial alignment, but only 5 percent show consistent alignment.

Even among Republican-identifying young men, 66% show partial alignment — while just 10% meet the threshold for consistent alignment.

Even where engagement is highest, ideology does not consolidate.

The issue-level data explain why.

Among young men, fewer than one-third agree that Islam poses a threat to American values (27%), that affirmative action disadvantages qualified white Americans (31%), or that young adults should prioritize marriage and family over career (31%). On climate, only one-in-four agree that concerns are exaggerated.

These are not peripheral ideas.

They are central to the framework.

Agreement does not compound.

It thins.

This is the core limitation of grievance-driven politics. It excels at diagnosis. It generates attention. But it fails to produce coherence.

The difference lies in how grievance is processed.

For many young men, grievance shows up as a demand for recognition — a sense of being dismissed or talked down to. Rhetoric that validates that feeling can be energizing, even without full agreement.

For many young women, grievance accumulates as risk — economic, social, and physical. As a result, women are more skeptical of frameworks that add obligation, rigidity, or uncertainty.

That difference explains what we see throughout this analysis: engagement without consolidation among men, and faster exit among women.

It’s not that women are less angry.

It’s that they are less willing to gamble.

The Bottom Line

The data do not show a generation moving right or left.

They show a generation refusing to lock in.

Young Americans — especially young men — are willing to engage, listen, and test ideas. But they are far less willing to commit to rigid ideological frameworks, particularly those that ask them to absorb risk, accept enforcement, or trade flexibility for certainty.

That distinction will shape what comes next.

For Turning Point USA, the challenge is not visibility. It is durability. An organization built on energy and confrontation can keep attracting attention — but without deeper alignment, each new cohort must be activated from scratch.

Erika Kirk inherits that reality.

Donald Trump succeeded by functioning as the coherence himself. His personal authority substituted for ideological consistency. That model does not transfer easily to institutions or successors.

What comes next — for Republicans, Democrats, and youth politics more broadly — will depend on who can reduce risk, not just name grievance.

The future of youth politics will not belong to whoever is loudest.

It will belong to whoever can answer a simpler, harder question:

Will this make my life more stable, more predictable, and less fragile?

Until an ideology can answer that credibly, alignment will remain elusive.

Q: What did one Deadhead say to the other after the weed ran out?

A: This music sucks.

Same story here.

Great analysis.